The Super Hornet Just Turned 30 and the Wright Brothers’ First Powered Flight

From the Wright brothers lifting off windswept dunes to Super Hornets ruling the decks, 120 years of relentless innovation have transformed fragile dreams into aviation’s cutting edge

“We have people that have built entire careers designing and working on this airplane. It means a ton to the people that are here. It is an iconic part of what we’ve done here in Saint Louis.”

—Mark Sears, vice president and program manager of Fighter Programs at Boeing.

Mission Briefing

On November 29, 1995, in St. Louis. The prototype F/A-18E Super Hornet roared off the runway for the first time, sunlight glinting off its fresh paint. That single takeoff launched a new era for U.S. carrier aviation, a legacy that still soars strong three decades later.

Boeing Celebrates Super Hornet’s 30th Anniversary

Around three decades ago in St. Louis, not far from Lambert Airport, the very first F/A-18E Super Hornet took shape and thundered into the sky for the first time. The Super Hornet didn’t come easy.

Born out of a time when budgets were tight and programs were getting the axe, it faced its share of doubters, some in Congress, others right in the Navy’s own ranks. Yet, the Navy pressed on, ordering the jet in 1992 after shelving other ambitious projects and even halting upgrades to the legendary F-14 Tomcat.

What rolled out of the St. Louis factory was no simple refresh. The Super Hornet kept the Hornet name but was a beast of its own: a quarter larger, with a third more fuel, a wing built from scratch, and systems designed for modern warfighting.

The prototype’s maiden flight on November 29, 1995, flown by test pilot Fred Madenwald, was more than a test run. It was a statement. Against the odds, the Super Hornet was here to stay.

From that moment on, the Super Hornet earned its stripes as the backbone of Navy carrier aviation, evolving with each chapter and still rising to new challenges today.

Features: The Super Hornet Up Close

Three decades on, the Super Hornet still rules the deck. Since that prototype took to the Missouri sky, the F/A-18E/F has flown into legend—now surpassing a staggering 12 million flight hours as of August 2025. This milestone doesn’t just mark time; it cements the Hornet and its electronic warfare sibling, the Growler, as the backbone of U.S. Naval Aviation.

Today, about 550 Super Hornets and 150 Growlers stand ready across the fleet, while the Marine Corps fields another 180 “Legacy” Hornets. These aircraft have carried generations of aviators across blue water and into harm’s way, proving their worth in every role from long-range strike to air defense.

Even as the Navy eyes the sleek lines of the F-35C and dreams up the next generation with the F/A-XX, the Super Hornet remains indispensable, a trusted workhorse and a linchpin for carrier strike groups well into the 2040s. The story of this aircraft isn’t just about numbers—it’s about endurance, adaptation, and a legacy that keeps climbing.

Let me walk you through what sets her apart, spec sheet style:

Primary Function: Multi-role attack and fighter aircraft

Contractor: McDonnell Douglas (now The Boeing Company)

Date Deployed: First flight in November 1995. Initial Operational Capability (IOC) in September 2001 with VFA-115, NAS Lemoore, California. First cruise for VFA-115 is onboard the USS Abraham Lincoln. Unit Cost: $67.4 million (FY21)

Propulsion: Two F414-GE-400 turbofan engines. 22,000 pounds (9,977 kg) static thrust per engine

Length: 60.3 feet (18.5 meters)

Height: 16 feet (4.87 meters)

Wingspan: 44.9 feet (13.68 meters)

Weight: Maximum Take Off Gross Weight is 66,000 pounds (29,932 kg)

Airspeed: Mach 1.8+

Ceiling: 50,000+ feet

Range: Combat: 1,275 nautical miles (2,346 kilometers), clean plus two AIM-9s

Ferry: 1,660 nautical miles (3,054 kilometers), two AIM-9s, three 480-gallon tanks retained

Crew: A, C and E models: One B, D and F models: Two

Armament: One M61A1/A2 Vulcan 20mm cannon; AIM 9 Sidewinder, AIM-9X (projected), AIM 7 Sparrow, AIM-120 AMRAAM, Harpoon, Harm, SLAM, SLAM-ER (projected), Maverick missiles; Joint Stand-Off Weapon (JSOW); Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM); Data Link Pod; Paveway Laser Guided Bomb; various general-purpose bombs, mines and rockets

Super Hornet: A Backbone for U.S. Power and a Bridge for Allied Strength

The F/A-18E/F Super Hornet might not have the Hollywood spotlight of the F-14 or the next-gen allure of the F-35, but its legacy is just as profound. This is the jet that rescued the country’s naval aviation from a crossroads, proving itself a reliable and versatile mainstay.

The Super Hornet’s tale is one of smart evolution. It showed that dominance can come from steady progress, not just revolutions. It’s the quiet workhorse of the carrier deck, shifting seamlessly from fighter to bomber to tanker, always ready for the next challenge.

While others grab the headlines, the Super Hornet gets the job done, mission after mission. As new aircraft join the fleet, this unsung hero keeps standing guard, the steady backbone of America’s carriers.

Additionally, the Super Hornet’s value extends far beyond American decks. It’s a force multiplier for U.S. allies around the globe. Nations like Australia, Canada, and Finland have put their trust in Hornets and Super Hornets, making joint training and coalition missions far more seamless.

When allies fly the same aircraft, it’s easier to share tactics, streamline logistics, and keep the wheels of cooperation turning smoothly. That commonality means pilots and maintainers can slip into allied squadrons with ease, and supply chains hum along without a hitch.

For countries that can’t afford to develop their own jet fighters, the Super Hornet is a proven, ready-made solution. It offers air defense, strike, and maritime power in a single package; battle-tested and ready for action.

By choosing American-built jets, these air forces not only strengthen their own capabilities but also deepen ties with the U.S., fostering a security network that spans oceans and generations.

This Week in Aviation History

The Wright Brothers’ First Powered Flight

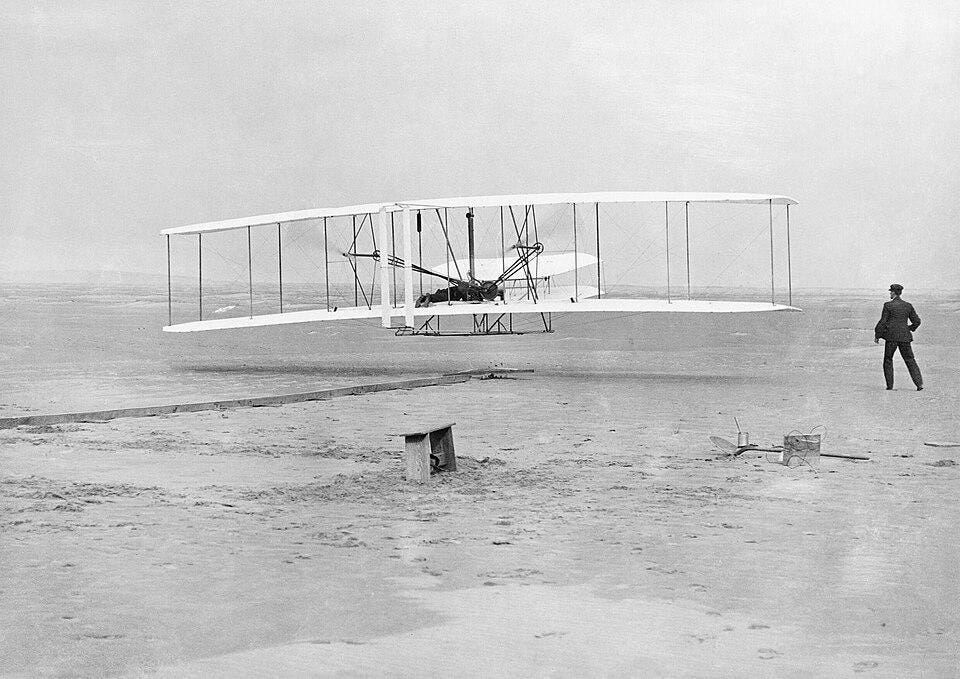

On the windswept sands of Kill Devil Hills (near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina) on December 17, 1903, after countless tries, Orville Wright finally coaxed the Wright Flyer into the air. It is a fragile leap that lasted only 12 seconds and carried him 120 feet at a brisk 6.8 miles per hour. In that short moment, the dream of flight became a living, soaring reality.

The Birth of Powered Flight: Why It Matters

The invention of the Kitty Hawk flyer was no accident or lucky break. Wilbur and Orville Wright spent four years immersed in research and hands-on experimenting, pioneering the very tools of modern aeronautical engineering. They built and tested gliders, crafted their own wind tunnel, and ran flight trials to perfect their vision, laying the foundation for every aircraft that would follow.

By the spring of 1903, the brothers were ready to roll the dice on powered flight. The Flyer itself was a sturdier, upsized version of their 1902 glider, but the real leap forward was the propulsion system.

With their trusted bicycle shop mechanic, Charlie Taylor, they engineered a compact twelve-horsepower gasoline engine. But the real genius was in the propellers; two elegantly simple blades, designed as spinning wings to create horizontal thrust. This idea, spinning an airfoil to “lift” the airplane forward, was one of the most creative leaps in aviation history.

Mounted behind the wings and linked by a chain-and-sprocket system to the engine nestled on the bottom wing, these propellers turned a humble canvas craft into the world’s first true airplane.

After days of tinkering, setbacks, and wild hope, Orville Wright eased himself onto the spindly Wright Flyer, canvas stretched tight, wood creaking in the chill. With a sputtering engine and a leap of faith, the Flyer slipped from its launching rail and defied gravity for 12 unforgettable seconds, covering 120 feet at a brisk 6.8 miles per hour. One of only five witnesses managed to snap a photograph as history took flight.

Not content with a single triumph, the Wright brothers took turns at the controls, coaxing three more flights from their pioneering machine. The final hop soared 852 feet in 59 seconds, never more than 10 feet above the sandy earth.

The Flyer’s day ended battered by the wind, wrecked beyond repair—but its legend was beginning. Orville carefully shipped the remains home to Ohio. After a stint in London, the restored Flyer found its forever home at the Smithsonian, where it stands as a beacon for dreamers.

The Wrights pressed on, building ever more daring machines, flying 24 miles nonstop by 1905. Soon, aircraft would thunder above the trenches of World War I, bridge cities on the first commercial routes, and carry mail across a nation. But the journey all began with a short, shaky hop on a cold Carolina morning, a moment that set humanity’s sights forever skyward.

The Wright Flyer: A Closer Look

The Wright brothers launched us into the aerial age with the world’s first successful powered flight, but that moment was the summit of four years of patient, inventive work. Wilbur and Orville didn’t simply build a plane. They built three full-sized gliders, tested and refined every detail, and used their own wind tunnel to unlock the secrets of flight.

Their genius wasn’t just in getting off the ground, but in pioneering the fundamentals of aeronautical engineering. From wind tunnel experiments to rigorous flight tests, the Wrights crafted the very foundation of modern aviation, proving that the dream of controlled, powered flight could be realized and charting the path for generations of aviators to come.

Here’s the simple anatomy of the world’s first airplane, invented by the Wright Brothers:

Wingspan: 12.3 m (40 ft 4 in)

Length: 6.4 m (21 ft 1 in)

Height: 2.8 m (9 ft 4 in)

Weight: Empty, 274 kg (605 lb); Gross, 341 kg (750 lb)

Airframe: Wood

Fabric Covering: Muslin

Engine Crankcase: Aluminum

Physical Description: Canard biplane with one 12-horsepower Wright horizontal four-cylinder engine driving two pusher propellers via sprocket-and-chain transmission system. Non-wheeled, linear skids act as landing gear. Natural fabric finish - no sealant or paint of any kind.

The Wright Flyer’s Legacy: Opening the Skies to Humanity

The Wright brothers did more than lift a fragile flyer into the air. They set the wheels of an industry in motion and gave wings to human ambition. Their breakthrough at Kitty Hawk unleashed a cascade of innovation that made flight a vital thread in the fabric of modern life.

More than a century later, their daring spirit still inspires pilots, engineers, and dreamers to look skyward and reach higher.

Yet what truly sets the Wrights apart is their perseverance. They met every setback and skeptical glance with determination, learning from each failure and never letting go of their vision. Their story is a living lesson that true progress is built on grit and relentless curiosity.

As we celebrate Wright Brothers Day, we not only honor their achievements but also look ahead. From electric aircraft to journeys beyond the atmosphere, every new step in aviation owes a debt to the foundation they built, and their dream of flight keeps evolving.

In Case You Missed It

All about the BUFF

Photo Outlet

Every issue of Hangar Flying with Tog gets you a free image that I’ve taken at airshows:

Feel free to use these photos however you like, if you choose to tag me, I am @pilotphotog on all social platforms. Thanks!

Post Flight Debrief

Like what you’re reading? Stay in the loop by signing up below—it’s quick, easy, and always free.

This newsletter will always be free for everyone, but if you want to go further, support the mission, and unlock bonus content like the Midweek Sortie, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this flight crew flying—and I couldn’t do it without you.

– Tog