Global Reach, Nuclear Ambition: A Tale of Two Airlifters

From the rugged versatility of the C-17 Globemaster III to the daring atomic experiments of the NB-36H, this week we spotlight how the U.S. Air Force pushed the limits of logistics and technology.

"That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." - Neil Armstrong, on July 20, 1969.

Mission Briefing

C-17 Globemaster III: The Go-Anywhere Workhorse of the U.S. Air Force

Cargo aircraft seldom get the spotlight. However, whether its dirt runways in war zones to rapid evacuations and humanitarian relief, the C-17 Globemaster III has become one of the most dependable and versatile aircraft in the United States Air Force. Designed to combine strategic reach with tactical flexibility, this rugged airlifter has redefined what a heavy transport can do—both on paper and in the real world.

Born from Necessity

The C-17’s story began in December 1979, when the U.S. Department of Defense launched the Cargo-Experimental (C-X) program. The goal? To find a jet-powered replacement for the aging C-141 Starlifter with short takeoff and landing (STOL) capability, a rear cargo ramp, and the ability to deploy troops and heavy equipment directly into combat zones. McDonnell Douglas responded by scaling up their earlier YC-15 prototype—originally designed to replace the C-130—and won the contract in August 1981 with a bold new design: the C-17.

After years of development setbacks, delays, and redesigns—including a major issue with static wing tests in 1992—the C-17 finally made its first flight on September 15, 1991, from Long Beach, California. Testing at Edwards AFB and strong political pressure nearly ended the program, but by 1995, the kinks were worked out and the first squadron was declared operational.

In 1997, Boeing merged with McDonnell Douglas, giving the Globemaster III a new lease on life. Thanks to improved reliability and a more favorable price, orders resumed. In total, the USAF would eventually acquire 224 C-17s. The aircraft also gained international attention, joining the air forces of the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, India, and several others.

Airdrop to Aeromedical: The C-17’s Mission Set

What sets the C-17 apart isn’t just its size—it’s the sheer range of missions it can perform. Its cavernous cargo hold can carry:

One M1 Abrams tank

Three Bradley IFVs

Three AH-64 Apaches

18 standard 88"x108" cargo pallets

Up to 102 fully equipped troops

48 litter patients and 54 ambulatory casualties

The aircraft’s rear ramp allows for rapid loading and unloading, and the cargo floor can switch from flat panels to roller conveyors in minutes. It’s just as capable of air-dropping paratroopers or supplies over hostile territory as it is delivering humanitarian aid to remote regions.

Powered by four Pratt & Whitney F117-PW-100 turbofans, each producing 44,400 pounds of thrust, the C-17 cruises at 570 mph and reaches a service ceiling of 45,000 feet. Its maximum unrefueled range is 4,700 nautical miles, but air-to-air refueling gives it global reach with virtually no limits.

Short Runways, Big Impact

The C-17’s short-field performance is nothing short of legendary. It set 33 world records during its flight testing phase, including one for taking off and landing in less than 1,400 feet with a 44,000-pound payload.

This is made possible by its “blown flaps” system—a form of powered lift that uses engine exhaust over the trailing edge flaps to generate additional lift at low speeds. Combined with reverse thrust capability (even in flight), the aircraft can land on austere runways as short as 3,000 feet and turn around on the ground in under 80 feet.

Its robust landing gear and ability to back under its own power allow the C-17 to go where most aircraft its size simply can’t. Whether it’s an airstrip in Afghanistan, a jungle clearing in South America, or a hurricane-ravaged island in the Pacific, the Globemaster III gets in, gets out, and gets the job done.

Legacy in the Sky

Perhaps no image better captures the C-17’s legacy than the now-famous August 15, 2021 evacuation from Kabul, when a single U.S. Air Force C-17 safely transported 823 evacuees—the most ever recorded on a single flight.

From the battlefield to disaster zones, the C-17 Globemaster III continues to prove why it’s one of the most important aircraft in modern Air Force history. It’s not just a heavy lifter—it's a global responder, a combat enabler, and a symbol of unmatched logistical power.

This Week in Aviation History

20 July 1955 – The Flight of the Flying Reactor: At Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas, the Convair NB-36H took to the skies for the first time—ushering in one of the most ambitious and unusual experiments of the Cold War: the quest for a nuclear-powered aircraft.

The idea behind the NB-36H, often dubbed the "Convair Crusader" or simply the “Nuclear Test Aircraft,” was to test whether a nuclear reactor could realistically power an airplane. At its core was a bold concept: instead of burning fuel to create thrust, a nuclear reactor would heat compressed air to generate propulsion. In theory, this would allow unlimited range and loiter time—ideal for Cold War-era strategic bombers. I made a full video on the B-36, including its nuclear test phase, you can check it out by clicking this link.

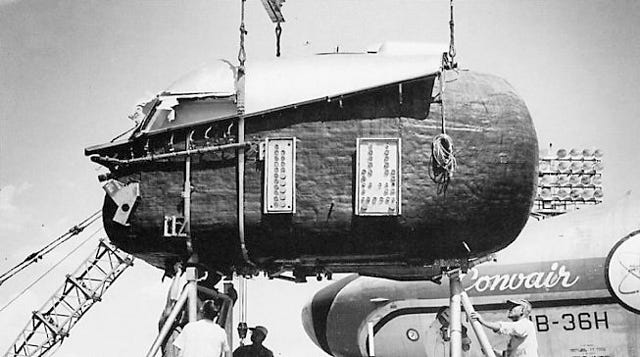

But the real purpose of the NB-36H wasn’t propulsion. Instead, it served as a flying laboratory to study how a nuclear reactor could be safely operated in flight and, crucially, how to protect the crew from radiation. To do this, Convair modified the airframe of a B-36H-20-CF Peacemaker that had been heavily damaged by a tornado at Carswell in 1952. The aircraft, serial number 51-5712, was rebuilt with a massive 11-ton lead- and rubber-lined crew capsule to shield the pilots from radiation. In June 1956, its designation changed from XB-36H to NB-36H.

In the aircraft’s aft bomb bay, engineers installed a one-megawatt Aircraft Shield Test Reactor developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The 35,000-pound reactor was fully operational, though it never powered the aircraft—it was only used to assess shielding requirements and potential effects on aircraft systems.

Like all B-36s, the NB-36H was a hybrid of piston and jet power: six Pratt & Whitney R-4360-53 Wasp Major radial engines and four General Electric J47-GE-19 turbojets gave it a top speed of 420 mph and a service ceiling of 47,000 feet.

Between 1955 and 1957, the NB-36H completed 47 test flights totaling 215 hours. Each mission was accompanied by a dedicated chase plane and strict safety protocols in case of a crash involving the reactor. Despite its success in demonstrating safe airborne reactor operation, the program was ultimately canceled in 1958. The aircraft was scrapped soon after.

In the end, the dream of a nuclear-powered bomber faded into history—but the NB-36H remains a powerful reminder of the era’s audacious aerospace experimentation and the lengths the U.S. Air Force was willing to go to maintain a technological edge.

In Case You Missed It

Here’s my foray into long form videos - all about the F-35:

Photo Outlet

Every issue of Hangar Flying with Tog gets you a free image that I’ve taken at airshows:

Feel free to use these photos however you like, if you choose to tag me, I am @pilotphotog on all social platforms. Thanks!

Post Flight Debrief

Like what you’re reading? Stay in the loop by signing up below—it’s quick, easy, and always free.

This newsletter will always be free for everyone, but if you want to go further, support the mission, and unlock bonus content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this flight crew flying—and I couldn’t do it without you.

– Tog

We flew Hueys in instrument training and I flew several aircraft during my time in the Army. I flew CH-34s and the Bell 47 (OH-13) in Germany Vietnam was all Huey time. I did my rotary wing training in an OH-23D. I was dual rated and flew the Bird

Dog and Beaver. The Beaver (U-6) was my favorite fixed wing.

I was a Huey pilot and transitioned into the Chinook. I did a turn around into the MOI program and was qualified as an instructor in the Chinook (CH-47). I was assigned as an instrument instructor at a base in Germany and never saw another CH-47! That’s the Army for you.