Ghost Bat Gears Up: AIM-120 Test on Deck This December, Six Decades after Thor’s Announcement in Britain

Sixty-six years since Thor’s debut, another December milestone approaches: the MQ-28A’s first air-to-air missile launch, a moment that marks the next bold leap in allied airpower and echoes history’s

“Ghost Bat is the first military aircraft designed and built in Australia in more than 50 years.”

—Australian Government Defence

Mission Briefing

December’s set to crackle over the range as the MQ-28A Ghost Bat lines up for its first live-fire with an AIM-120, a moment thick with anticipation and the whine of jet turbines on the morning air. With Boeing and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) fast-tracking the test, you can almost taste the confidence in this drone’s sensors and split-second autonomy—a loyal wingman stepping right into the fight. What’s worth watching now is how the Ghost Bat’s sharpened claws might change the shape of air combat as we know it.

Ghost Bat Steps Up: No Longer Just the Wingman

The MQ-28A Ghost Bat is about to make some real noise out at Woomera this December, as Boeing and the Royal Australian Air Force line up for its first live-fire test with an AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM)—months ahead of what folks were expecting. This isn’t just a routine check-the-box; it’s the Ghost Bat stepping out of the loyal-wingman shadows and proving it can sling missiles, not just pass data and play wingman to the crewed jets.

The program started out with teamwork in mind, all about sharing info and supporting the main show, but bit by bit, the Ghost Bat’s been showing off—integrating with everything from Wedgetails to Tritons and F-35s, and handling autonomy and networking like it was born for it.

If that missile lights off and finds its mark, it won’t just validate the tech—it’ll put the Ghost Bat on the map as a frontline fighter in its own right, not just a tagalong drone. Sure, they’re keeping the details on weapons carriage and prior tests under wraps, but fast-tracking this live-fire says plenty about the confidence behind those composite wings.

Features: Ghost Bat Unleashes Its Arsenal

Word is, nobody’s seen proof yet that the Ghost Bat’s been through a proper captive-carry run with a dummy AMRAAM, which is usually the drill before any new bird gets to toss real missiles downrange. The details on what kind of internal weapons bays the MQ-28A is hiding are still locked up tight.

What’s clear, though, is that when the Ghost Bat heads out to Woomera for this December’s live-fire, it’ll be under “tactically relevant” conditions—no easy day at the range. Recent photos show some of the Block 1 Ghost Bats sporting what appear to be IRST sensors on their noses, possibly for target spotting during the upcoming test. There’s talk of swapping out the entire nose section for ISR or electronic warfare payloads, making this drone a bit of a shapeshifter.

Chances are, the Ghost Bat will take its shot at a drone target, showing it can take cues from off-board sensors and launch weapons on command—exactly the kind of skill that changes the game in a real fight. Maybe the E-7A Wedgetail, MQ-4C Triton, F-35A, or even the Growler will play backup, maybe not.

Either way, giving a UCAV (unmanned combat aerial vehicle) air-to-air teeth adds much-needed numbers in a peer fight and throws all sorts of problems at the enemy. Boeing and the RAAF have already proven the Ghost Bat can team up and play nice with the rest of the fleet.

Look at that June mission where two of them worked with a Wedgetail against a simulated target, all AI-driven and operator-guided from the E-7. For an aircraft that can taxi, take off, and land itself, it’s moving fast—and changing the rules as it goes.

Let’s take a quick tour of its standout features.

Multi-mission capability: surveillance, reconnaissance, electronic warfare and armed strike

designed to team with crewed aircraft

High performance/fighter-like

Networked, open-architecture system

Modular nose/payload bay

Ghost Bat: The US and Allies’ New Secret Weapon

The Ghost Bat isn’t just some prototype toy anymore—its march toward that AIM-120 live-fire test marks a real turning point for U.S. and allied airpower. They say it’s already rubbed elbows with the likes of the E-7A Wedgetail, MQ-4C Triton, and F-35A, showing it can team up and pass data just like the best of them.

That kind of networking is no small feat, especially when you realize those same platforms are flying with U.S. units and trusted allies around the globe. The Ghost Bat is growing up in the same coalition neighborhood, already tuned for interoperability.

Look at its modular nose, the way it handles like a fighter, and that open-architecture design—the sort of setup that lets any partner plug in their own gear. For the U.S., it’s a window into how you can stretch the legs of your fifth-gen jets and early-warning birds without putting a pilot at risk or breaking the bank.

For the alliance, it’s proof that partners like Australia aren’t just along for the ride anymore—they’re building the kind of advanced, adaptable systems that slot right in with American kit. Bottom line? The Ghost Bat is helping stitch together that distributed, networked airpower model everyone’s betting on for the next big fight.

Ghost Bat’s steady march toward weapons integration is a sure sign that unmanned systems are moving from the sidelines to center stage in allied airpower. Expect better developments in the future, and those drones will dive deeper into autonomy and teamwork, carving out mission roles nobody would’ve dreamed up a few years back.

This Week in Aviation History

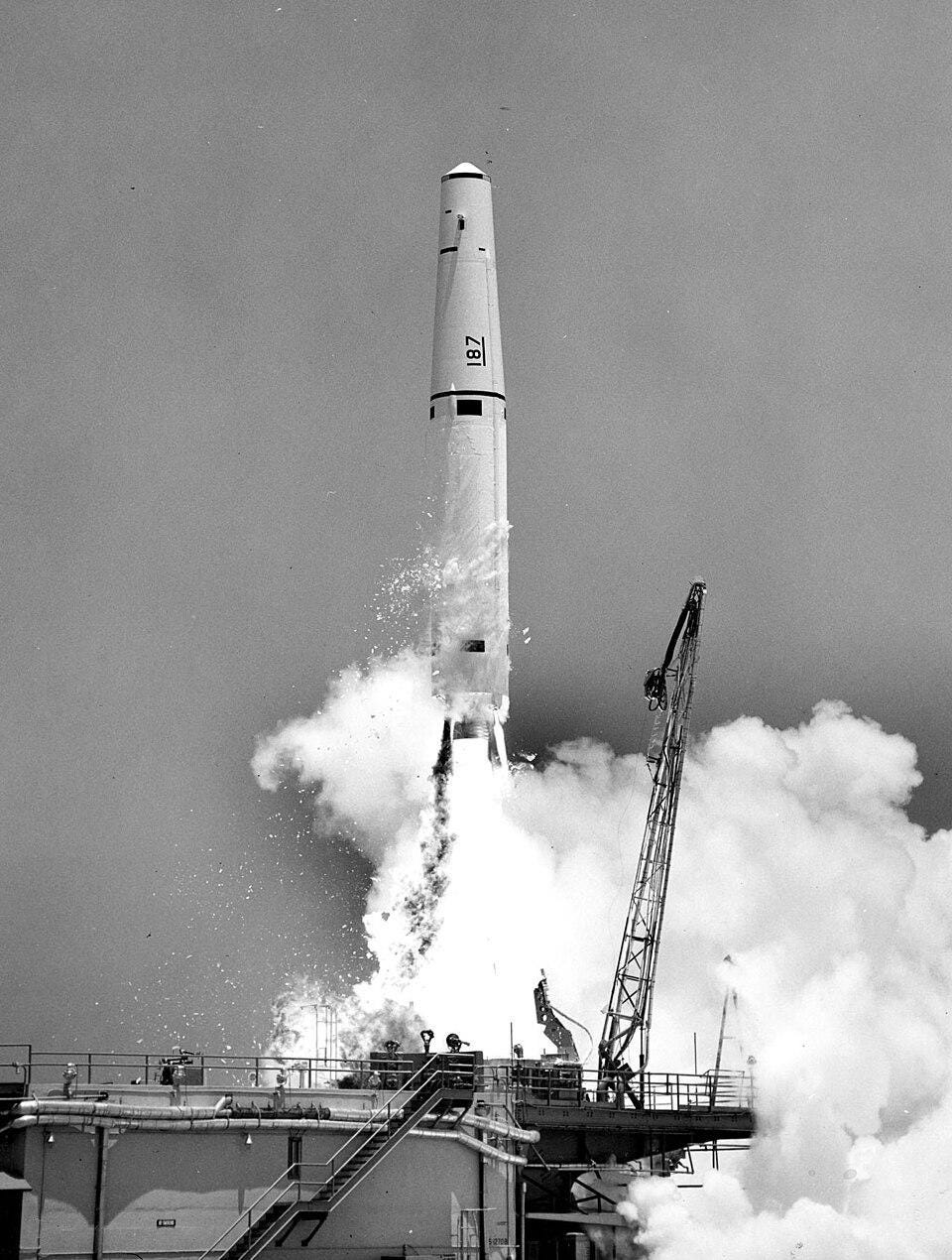

The winter air is sharp with anticipation, as word comes down on December 9, 1959: the PGM-17 Thor missile system has officially joined the Royal Air Force’s front line. In that moment, Britain’s defense leapt boldly into the new missile age, forever changing the shape of the skies above.

When Strategy Became Steel: Thor on the Line

Right in the heart of the House of Commons. The Secretary of State for Air stood up, all eyes on him, and announced that after successful test firings in the States and solid training back home, they were ready to declare the Thor missile system fit for duty.

That wasn’t just paperwork—this was the British Air Ministry officially putting Thor on the front line, giving the RAF a new kind of muscle overnight. From that day forward, the Thor missile wasn’t just a project or a promise; it was operational, standing watch as part of Britain’s defense. For anyone watching the skies back then, it was clear—a new era had just begun.

The late ’50s were a time of tough choices in Whitehall, with Harold Macmillan and Duncan Sandys flipping the old playbook on its head. Gone were the days of blanket air defense—Sandys argued that no fighter could stop a nuclear-armed missile, so Britain’s only shot at survival was to hold a credible threat to strike back. That meant putting faith in missiles, not only in squadrons of interceptors, and moving fast to keep up with the changing world.

So when the British Air Ministry stood up in December 1959 and declared the Thor IRBM force operational, it was more than just a systems check; it was the moment Sandys’ vision stepped off the drawing board and onto the flight line. Under the Anglo-American deal, the U.S. supplied the warheads, but it was British hands on the launch controls, dual-key and all. With Thor, Britain could now answer an attack immediately—something the vulnerable V-bombers couldn’t promise if the Soviets brought the surprise.

That single announcement said plenty: missiles were now the backbone of Britain’s defense, NATO’s nuclear front line had a new pillar, and the hard choices of the ’57 Defence White Paper were paying off. For everyone watching—friends and foes alike—it was clear that Britain’s future in the missile age had landed, live and on alert.

Thor Missile System: A Closer Look

The story of the Thor missile started in the shadowy dawn of the Cold War, when everyone on both sides of the Atlantic was racing to put a nuclear warhead on target before their rivals could blink. The SM-75, later called the PGM-17A Thor, was America’s quick-on-the-draw answer—a 1,500-mile-range missile designed to fill the gap while engineers sweated over true intercontinental birds. Thor’s roots ran deep in the Atlas ICBM program; she borrowed her engine, guidance, and warhead straight from Atlas, leaving only the airframe as new territory to chart.

From the moment Great Britain agreed to host four IRBM bases, Thor’s story became a transatlantic one. RAF crews manned the launch sites, but Uncle Sam kept the keys to the nuclear warheads, a true Cold War partnership with its own quirks.

After a few fiery setbacks, Thor finally roared to life with a successful flight in September ‘57—just in time for Sputnik to send the whole Western world’s pulse sky-high. Eisenhower, not wanting to be left behind, accelerated Thor’s development.

On the pad, Thor was a one-stage liquid-fueled rocket, gulping down liquid oxygen and kerosene, blasting up to 280 miles before letting its warhead coast to target. She took about 15 minutes to prep for launch, and 18 minutes later, her business was done.

Thor’s operational stint as an IRBM was brief—England hosted her from June ’59 to August ’63—but after that, she found new life. The Air Force used her for nuclear test shots, as an antisatellite weapon, and later, NASA and the USAF turned her reliable bones into a dependable space launcher.

Let’s dig into the nuts and bolts of the Thor missile system.

Warhead: Single W-49 in the kiloton range

Engines: One Rocketdyne LR79-NA-9 of 150,000 lbs thrust; two Rocketdyne LR101-NA vernier engines (for small thrust and direction adjustments) of 1,000 lbs thrust each

Guidance: All-inertial

Range: 1,500 miles

Length: 65 ft

Diameter: 8 ft

Weight: 110,000 lbs (fully fueled)

Forged in Trust: The True Legacy of Thor

The real legacy of the Thor missile isn’t just about rockets and warheads—it’s about the dawn of a partnership that changed everything between the U.S. and the U.K. Back in the Eisenhower years, when trust was gold and nuclear secrets were closely guarded,

Thor became the first real bridge: a nuclear system not just shared, but operated together. The RAF manned the launch pads, the Americans held the dual-key, and for the first time, both sides exchanged the kind of sensitive missile knowhow and warhead-handling procedures that used to be top secret.

That daily collaboration did more than get missiles ready—it built habits, routines, and trust that made later deals possible. Polaris submarines in Scotland, the Mutual Defence Agreement of 1958, even the big switch to U.S. Polaris missiles after the Nassau Conference—all of it got a running start thanks to Thor’s groundwork. When Britain’s own missile projects hit the skids, it was the habits and trust from the Thor years that kept them in the nuclear club.

Thor was never meant to be a permanent shield, but its political and strategic legacy is what really lasted. It proved the U.S. and U.K. could manage nukes as true partners—and that lesson shaped past and current Western strategy long after the last Thor left its silo.

In Case You Missed It

The Cold War did have an “anything goes” sort of feel to it - didn’t it?

Photo Outlet

Every issue of Hangar Flying with Tog gets you a free image that I’ve taken at airshows:

Feel free to use these photos however you like, if you choose to tag me, I am @pilotphotog on all social platforms. Thanks!

Post Flight Debrief

Like what you’re reading? Stay in the loop by signing up below—it’s quick, easy, and always free.

This newsletter will always be free for everyone, but if you want to go further, support the mission, and unlock bonus content like the Midweek Sortie, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this flight crew flying—and I couldn’t do it without you.

– Tog