Aging Aircraft Fleet amidst Modern Threats and Looking Back at the Order Before the Storm in 1941

Both stories show adaptation in power projection: in 1941 via agile mission task groupings, today via difficult modernization as aging platforms drain budgets, readiness, and operational flexibility.

“We have not 4,000 fighters but 2,000. They average not 8 years old but 28 years old. Our pilots are flying not 18 to 20 hours a month but six to eight hours a month. And we’re ready not for great-power competition but for counterinsurgency warfare.”

—Lt. Gen. Richard G. Moore, deputy chief of staff for plans and programs for the Air Force

Mission Briefing

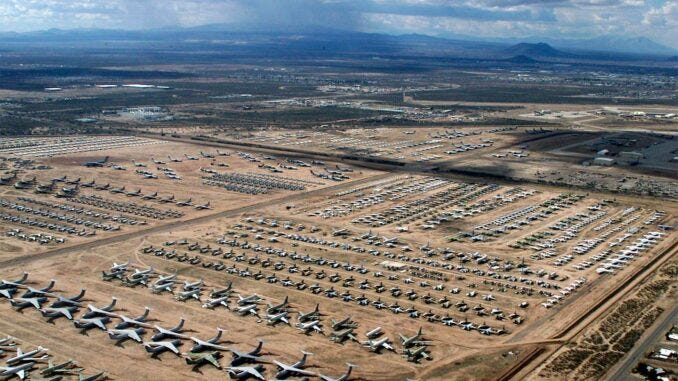

In 2025, the US Air Force finds itself flying into uncharted territory—the fleet is older and leaner than at any point in nearly eight decades. With the average aircraft approaching 32 years of age, America’s technological edge in airpower faces a crossroads. From strategic bombers to nimble fighters and watchful intelligence planes, these machines were born for another era, never meant to bear the weight of today’s missions for this long.

Strapped to the Past: Keeping Yesterday’s Jets Flying

Since its founding in 1947, the US Air Force has never faced an aging fleet quite like this. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the average aircraft was barely a teenager; between 10 and 15 years old. Even after the end of the Cold War, that number stayed under 25. But in 2025, the average age reaches 32, a number that signals more than just the passage of time; it marks a pivotal shift in America’s airpower story.

How did we get here? It’s a confluence of pressures. When the Soviet Union fell, the urgency for a massive fleet faded, so aircraft already in service simply flew longer. Then came years of hard deployments—Afghanistan, Iraq, the Middle East—missions that wore down airframes faster than anyone predicted. Add to this the skyrocketing cost of new technology, and suddenly, buying replacements slows to a crawl.

The result: a smaller, older, and more heavily used fleet, with wear and tear compounding every hour aloft. And as these birds age, maintenance becomes a monster. Spare parts aren’t rolling off assembly lines anymore. Sometimes, restarting production for a single component is the only option. That means longer downtime and ever-mounting costs.

This maintenance spiral is a trap. The more it costs to keep old jets flying, the less money there is for next-generation aircraft. Every dollar sunk into the past is a dollar stolen from the future. For some aircraft, support costs are climbing by several percent each year, outpacing even inflation.

Availability is the first casualty. Some fleets can’t keep more than 60% of their aircraft ready at any given time, leaving nearly 4 out of 10 grounded. For squadrons, this means tighter schedules, harder flying rotations, and more strain on crews. Flexibility dwindles, especially if the nation is called to fight at scale.

All these realities force tough choices. The Air Force must weigh whether to retire, extend, or replace their aging birds. Each option has its own risks, costs, and consequences. This is the crossroads where airpower’s future will be decided.

The Aging Birds

The B-52 Stratofortress is the perfect symbol of today’s challenge. Born in the early 1950s, this legendary bomber is on track to serve for over 80 years, an operational lifespan nobody could have imagined when its wings first took flight.

Its airframe was originally built for about 20,000 hours in the sky, yet some B-52s are now brushing up against, or even surpassing, that milestone thanks to repeated reinforcement programs.

Still, much of the aircraft—its engines, its core structure, its systems—remains anchored in designs from another era. Major maintenance calls for rare expertise and hard-to-find parts, often produced in tiny batches. The cost per flight hour keeps climbing, even as the B-52 remains useful for select missions.

The B-1B Lancer, which entered service in the 1980s, tells a different story. Decades of punishing low-level flights wore down its airframe far faster than anticipated. At times, fewer than half of these bombers have been mission-ready, with many sidelined for long and expensive repairs.

Then there’s the backbone of American reach: the in-flight refuelers. The KC-135 Stratotanker, dating back to the late ’50s, is now over 60 years old. Each inspection uncovers new cracks, corrosion, or outdated systems. Avionics upgrades have helped, but the old metal remains a limiting factor.

The KC-46 was meant to take the baton, but delays and technical issues—especially in its refueling and vision systems—have slowed its arrival. When a tanker goes down, it grounds not only itself but also any fighters or bombers that rely on its fuel.

F-15 Eagles and F-16 Fighting Falcons, many delivered in the 1980s, still form the backbone of the combat fleet. Designed for 4,000 to 6,000 hours, some now exceed 8,000, requiring deep inspections and costly repairs.

Meanwhile, the deliveries of the new F-35 Joint Strike Fighter are slipping behind schedule, with purchase numbers trimmed back as critical upgrades lag in the pipeline. The price of keeping these cutting-edge jets flying keeps climbing, yet they’re logging fewer hours in the air, and not enough are mission-ready when the call comes.

In other words, new birds are coming, but not fast enough. So, these aging workhorses remain essential, even as they face adversaries with far more modern technology.

The Price of Aging Fleets: Allied Airpower Impact

An aging, shrinking U.S. Air Force fleet isn’t just a matter of old jets on the ramp. It’s a story of diminishing airpower for every dollar spent, a shift that rewrites the calculus of deterrence for America and its allies alike.

For the United States, the effect is immediate and stark. Readiness and availability are squeezed ever tighter. A “maintenance spiral” eats up budgets and drives down aircraft availability, while overworked crews shoulder heavier loads. A smaller, older fleet stuck in the slow lane of modernization, even as China accelerates.

Fewer jets mean reduced pilot flying hours and the looming risk of burnout across the force. In the crucible of high-end conflict, this translates to fewer sorties, thinner surge capacity, and less ability to sustain operations on multiple fronts, especially with aging tankers and support aircraft.

Allies feel the squeeze too. U.S. airpower has long been the backbone of allied plans for air refueling, strike, ISR, and airlift. When American jets are less available, reinforcement timelines and operational mass become less certain.

Every grounded tanker can sideline multiple fighters or bombers, and delays in KC-46 fielding only add to the strain. The pressure is on for allies to invest in their own capacity, harden their bases, and stockpile munitions, because the margin for error in a crisis with China is narrowing fast.

The real question is, which modernization bets will truly break this spiral and which will just shift the problem into a new shape?

This Week in Aviation History

On February 1, 1941, the U.S. Navy charted a new course, organizing its forces into specialized mission groupings. At the helm was the U.S. Fleet, which brought together the Atlantic, Pacific, and Asiatic Fleets. Each with a theater to defend and a chapter to write. These fleets were crafted as both administrative engines and operational teams, designed to flex with the demands of war. Day to day, they took their orders from the Navy Department, guided by the steady hand of the commander-in-chief, Pacific Fleet.

When the Navy Learned to Fight in Packages

Following the February 1941 reorganization, America’s fleets were further broken down into area and task commands, each given a distinctive number. By March 1943, the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet had rolled out a standardized system: even numbers marked the Atlantic Fleet, odd numbers the Pacific.

Some numbers pointed to administrative or support roles, but the heart of the system was operational; numbered fleets split into nimble task forces. Each can respond to the demands of battle without the weight of administrative baggage. Task force commanders were free to focus on the fight, not the paperwork.

On February 1, 1941, the same day the new order took effect, the Pacific Fleet anchored its headquarters at Pearl Harbor; a place soon to be seared into history. Just ten months later, on December 7, Japanese aircraft unleashed devastation on Pearl and across Oahu, pulling America headlong into World War II.

The Pacific theater became a crucible for naval leadership, forging legends like Nimitz, Halsey, and Spruance. Here, some of the war’s most decisive blows were delivered; from the pivotal victory at Midway and fierce fighting in the Solomons, to the decisive battles of the Philippine Sea and Okinawa.

The Pacific war’s final act unfolded aboard the USS Missouri, where Japan’s surrender was signed on September 2, 1945. By then, the U.S. Navy boasted a staggering 6,768 ships, with the lion’s share prowling the Pacific.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic Fleet saw its own transformation. On that same February day, its commander was promoted to four-star rank, and in Puerto Rico, Ernest J. King raised his flag, readying for the coming storm.

The Atlantic fight became a brutal test of endurance. Guarding lifeline convoys, hunting U-boats, and keeping vital supplies flowing to Britain, then North Africa and Europe. It was teamwork—American, British, and Canadian navies; improved training; radar; and escort carriers—that finally tipped the balance, securing the Atlantic by 1943.

The Pacific Fleet and the Atlantic Fleet Forces

At the moment the bombs rained down on Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Fleet’s backbone was its nine battleships, split into three proud divisions. The first—USS Pennsylvania, USS Arizona, and USS Nevada—anchored the line.

The second followed with USS Tennessee, USS California, and USS Oklahoma. The third, just as formidable, consisted of USS Colorado, USS Maryland, and USS West Virginia. All but Arizona and Oklahoma survived the onslaught, patched up and returned to the fight, carrying the war’s burden all the way to 1945’s final victory.

After the guns fell silent, the Pacific Fleet’s mission evolved. They launched Operation Magic Carpet, turning warships into homeward-bound chariots, bringing America’s sons back from distant Pacific islands.

But peace was fleeting; soon, the fleet would answer new calls in Korea and Vietnam, proving that their watch over the Pacific never truly ends. Even today, the US Pacific Fleet stands guard from its historic base at Pearl Harbor, a living link to both triumph and sacrifice.

On the other side of the continent, the Atlantic Fleet experienced its own transformation on that pivotal February day in 1941. Rear Admiral Ernest J. King, aboard his flagship USS Texas in Culebra, Puerto Rico, exchanged his two-star pennant for four—the new Commander in Chief, United States Atlantic Fleet.

Over the next years, the fleet’s headquarters would shift across four flagships: USS Augusta, the storied USS Constellation, USS Vixen, and finally USS Pocono. In 1948, the command found its permanent home ashore in Norfolk, Virginia.

Postwar, America’s military underwent a thorough overhaul. On December 1, 1947, Congress created the unified United States Atlantic Command, co-locating its nerve center with the Atlantic Fleet. Admiral William H.P. Blandy, already at the fleet’s helm, became the first Commander in Chief of this new command; a role that would later expand, until the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1985 separated the two commands.

Let’s take a closer look at two-storied carriers from each fleet: the resilient USS Pennsylvania of the Pacific and the distinguished USS Augusta of the Atlantic.

USS Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania class battleship:

Displacement: 31,400 tons (normal / 35,929 tons (full load)

Length: 608’

Beam: 106’3”

Draft: 33’6”

Speed: 21 knots

Armament: 4x3 14”/45, 8x2 5”/38, 10x4 40mm, 22x2 20mm, 27x1 20mm, 8x1 .50-caliber MG, 2 21” tt; 3planes

Complement: 2,555

Propulsion: Steam turbines, 12 boilers, 4 shafts, 31,500 hp

Built at Newport News and commissioned 12 June 1916

Reconstructed at Philadelphia Navy Yard 1 June 1929--8 May 1931

USS Augusta

Northampton class Heavy Cruiser:

Displacement: 14,300 tons (full load)

Length: 600’3”

Beam: 66’1”

Draft: 24’

Speed: 32.5 knots

Armament: 3x3 8”/55, 4x2 5”/25 DP, 4x2 40mm, 4x4 40mm, 22 20mm, 3 planes (SC-1)

Complement: 1,155

Propulsion: Geared turbine engines, 8 boilers, 4 shafts, 107,000 shaft hp

Built at Newport News, and commissioned 30 January 1931

The Enduring Contrail of the US Fleet Forces Command

The February 1, 1941, reorganization left a lasting mark on how America fights at sea by shaping forces around the mission rather than rigid formations. As the Navy Department revived the Atlantic, Pacific, and Asiatic Fleets and clarified command just as the nation rushed toward war, it also seeded a culture of flexibility.

Ships, aircraft, and support elements could now be swiftly assembled into task forces tailored to a specific mission, then reconfigured or dissolved as the mission evolved. This mindset powered the Navy through World War II: from defending convoys and hunting submarines in the Atlantic to launching fast carrier strikes and amphibious assaults in the Pacific, all without reinventing the wheel for every new operation.

That legacy endures. Today’s Navy still builds adaptable task forces and strike groups, scaling and shaping its power for everything from deterrence to crisis response. The language of modern doctrine—flexible, responsive, sea-based strike groups—echoes the 1941 leap toward speed and clarity.

Back then, these mission groupings readied America for the coming storm; now, the same principle (organize fast, adapt faster) remains the cornerstone for credible sea power in a world of constant threats and shifting challenges.

In Case You Missed It

Photo Outlet

Every issue of Hangar Flying with Tog gets you a free image that I’ve taken at airshows:

Feel free to use these photos however you like. If you choose to tag me, I am @pilotphotog on all social platforms. Thanks!

Post Flight Debrief

Like what you’re reading? Stay in the loop by signing up below—it’s quick, easy, and always free.

This newsletter will always be free for everyone, but if you want to go further, support the mission, and unlock bonus content like the Midweek Sortie, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this flight crew flying—and I couldn’t do it without you.

– Tog