The Navy’s Newest Kennedy Carrier Sets Sail and Remembering the Time when USS Cusk Fires the Loon

From launching the first sea-based guided missiles to launching the next generation of sea-based airpower — the U.S. keeps reinventing how it projects force from the ocean.

This huge milestone is the result of the selfless teamwork and unwavering commitment by our incredible shipbuilders, suppliers, and ship’s force crew. We wish them a safe and successful time at sea!

—HII, America’s largest shipbuilder, Twitter Post

Mission Briefing

On January 28, 2026, the future USS John F. Kennedy (CVN 79), the Navy’s next Gerald R. Ford-class supercarrier, powered away from Newport News and surged into open waters for the first time. Her maiden voyage into manufacturer sea trials marked the dawn of a new era in American sea power.

CVN-79’s First Test of the Open Sea

The story of the USS John F. Kennedy (CVN 79) begins, fittingly, at the heartbeat of American carrier construction. The Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) shipyard in Newport News, Virginia. It was here, in 2015, that the keel was laid for the Navy’s next great supercarrier, continuing a tradition that has launched every nuclear-powered flattop in the fleet.

Yet, the journey from dry dock to open ocean would prove longer than most. For eleven years, the Kennedy took shape under the watchful eyes of shipbuilders and sailors alike. A span notably longer than that of her elder sister, the USS Gerald R. Ford, which was laid down in 2009 and slipped her moorings for sea trials by 2017.

What slowed Kennedy’s debut? The world changed in those years. The COVID-19 pandemic struck, sending shockwaves through labor forces and supply chains, but that was only part of the tale.

Congress, with an eye toward the future, mandated that Kennedy be delivered ready to operate the Navy’s cutting-edge F-35C Lightning II fighters from day one. In contrast, the Ford herself—though the most modern carrier afloat—has yet to undergo the modifications needed for the stealth jet.

These new requirements, combined with the pandemic’s disruptions, nudged the Kennedys’ delivery date ever further, even as the venerable USS Nimitz (CVN 68) wrapped up her final deployment and prepared for retirement. For a few years, the Navy will have to make do with just ten active carriers, dipping below the congressionally mandated minimum of eleven.

Normally, a second-in-class ship enjoys a swifter path through trials, learning the lessons and avoiding the pitfalls of its trailblazing predecessor. But Kennedy is no simple copy. Major design changes set her apart.

Most notably, the switch from Ford’s unique combination of AN/SPY-3 and AN/SPY-4 radars to the new AN/SPY-6(V)3 system, a technology shared in a different form with the latest Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. The result? A visibly different “island” silhouette atop Kennedy’s flight deck, signaling bigger changes beneath the steel.

Still, some innovations carry over from the Ford. The Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS), Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG), and Advanced Weapons Elevator (AWE) are all part of Kennedy’s DNA. Each of these advanced systems has had its share of growing pains.

The last AWE aboard Ford wasn’t installed until 2021, a full four years after the ship had joined the fleet. EMALS and AAG, while now more reliable, still fall short of the Navy’s ambitious targets, their complexity a double-edged sword—offering precision and efficiency, but demanding new levels of maintenance and expertise.

The debate over these modern systems has even reached the highest levels. During his time in office, President Donald Trump criticized EMALS and AAG, vowing in 2025 to restore steam catapults and hydraulic elevators by executive order. It is a move that, yet, remains only a promise.

While many sailors appreciate the rugged dependability of legacy gear, the Navy’s leadership sees the future in the smooth, adjustable power of electromagnetics, which reduces airframe stress and offers more flexible operations.

Until her official commissioning, the ship was known as the Pre-Commissioning Unit (PCU) John F. Kennedy. Since 2019, naval personnel have been assigned to the Kennedy, learning her systems, tending to her needs, and preparing for the day she would leave the shipyard’s embrace.

As sea trials begin, these sailors—already at home aboard their ship—will be at the heart of the action, testing every system and charting the course for the Kennedy’s future. Even the ship’s store has been stocked in anticipation, a small but meaningful sign that life aboard is stirring to full speed.

As the Kennedy sets sail for her first sea trials, she carries with her not just the hopes of her crew, but the legacy of a shipyard, the weight of new technology, and the promise of a new era in American sea power. The world will be watching as she carves her wake into the open ocean, a symbol of resilience, innovation, and the unbroken spirit of naval aviation.

USS John F. Kennedy (CVN 79): A Closer Look

Keel Laid: 22 August 2015

Christening: 7 December 2019

Commissioning: Upon completion of ship construction.

Armament:

Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile

Rolling Airframe Missile

CIWS (Close-In Weapons System)

Propulsion: Two nuclear reactors, four shafts

Displacement: 100,000 long tons full load

Speed: 30+ knots (34.5+ mph)

Flight Deck Width: 256 feet

Height: 134 feet

Length: 1,106 feet

Builder: Huntington Ingalls Industries Newport News Shipbuilding Division

Ship’s Sponsor: Ambassador Caroline Kennedy

Motto: “Serve with Courage”

First Wake of a Future Fleet: CVN-79 and the Return of Sea-Based Airpower

CVN-79, the USS John F. Kennedy, is more than just another aircraft carrier—it’s the U.S. Navy’s renewed bet on sea-based airpower for a new era of warfare. This next-generation supercarrier is designed not only as a floating airbase, but as a fortress capable of surviving and striking back in a missile-heavy, fiercely contested battlespace.

Its 2026 builder’s trials are more than a technical hurdle; they’re the first real test of the advanced systems that will keep its air wing launching sorties and enduring in combat far from safe harbors.

For America, Kennedy boosts the Navy’s ability to project power anywhere, anytime—unbound by host-nation permissions and agile enough to keep adversaries guessing.

For allies, it’s a centerpiece for coalition operations, offering a platform where partner navies can train, operate, and fight side by side, supported by integrated defenses and shared tactics.

The Kennedy also marks a leap forward in technology, fielding the SPY-6(V)3 radar and a modernized self-defense suite, making it a resilient command node within the fleet’s wider web.

As CVN-79 transitions from sea trials to operational service, it’s a powerful signal: American carrier aviation is evolving, ship by ship, to meet the demands of tomorrow’s high-end maritime conflicts.

This Week in Aviation History

On February 12, 1947, history was made off the California coast as the USS Cusk launched the Loon, the world’s first submarine-fired missile. The German V-1 and its American twin inspired a flurry of postwar innovation, evident in the Navy’s experimental “Gorgons” that once lined Rocket Row in the McDonnell Space Hangar. The late 1940s and early 1950s marked the dawn of America’s fascination with cruise missiles, fueling a new era of military experimentation and ambition.

From Silent Hull to Guided Fire: USS Cusk Launches the Loon

In the wake of World War II, the United States stood at a crossroads of technological possibility. The war had pushed the boundaries of both submarine and missile design, and American military planners quickly saw the potential in merging these advancements to counter the looming Soviet threat. The race was on to build a new kind of deterrent: a submarine that could launch guided missiles, projecting power in ways never before imagined.

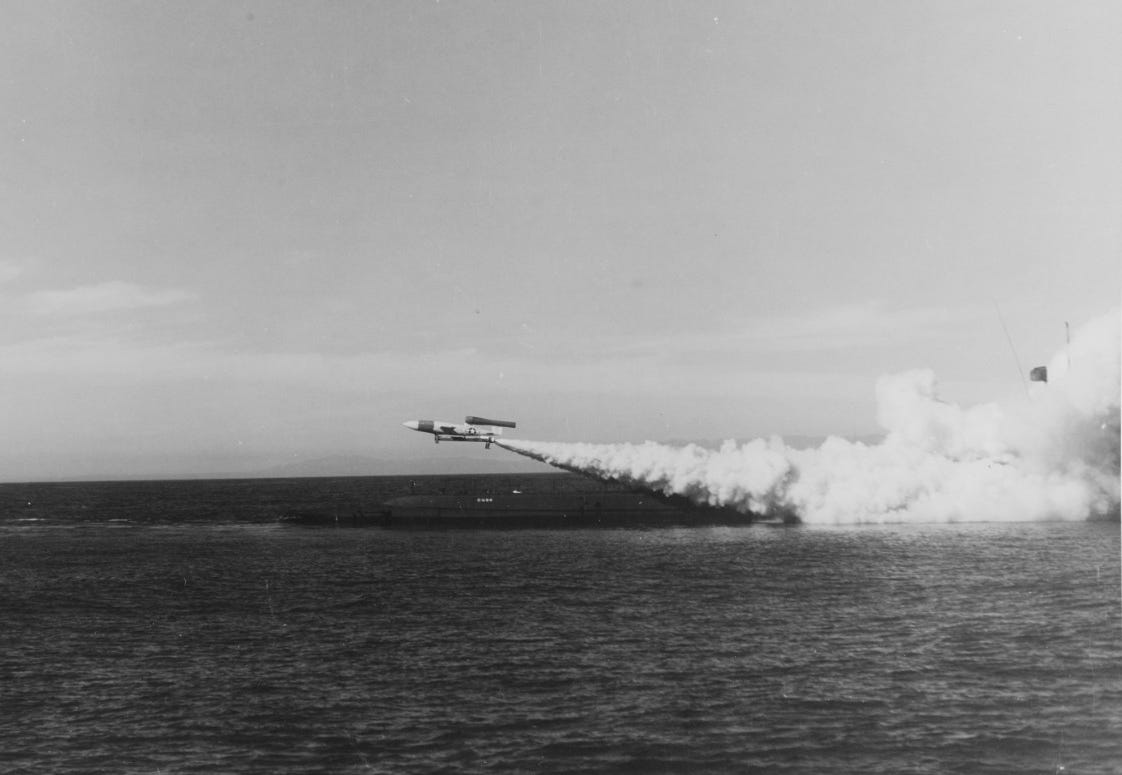

This vision took a giant leap forward in 1947. The USS Cusk (SS-348), a Balao-class submarine retrofitted with an airtight missile hangar and launch ramp behind its sail, made history by firing a Loon missile off the California coast. While the Cusk had to surface for the launch—true underwater missile launches would come later—this event marked the first successful guided-missile launch from a submarine, a moment that would echo through decades of naval innovation.

The Loon itself was an American adaptation of the infamous German V-1 cruise missile. During the war, the V-1—nicknamed “doodlebug” or “buzz bomb” for its distinctive, rattling pulsejet engine—had terrorized London and Antwerp. Over 22,000 were launched by the Luftwaffe, though many failed or were intercepted.

Despite its shortcomings and failure to turn the tide for the Nazis, the V-1 left a deep impression on Allied commanders. Determined to harness this technology, American engineers worked feverishly to reverse-engineer the V-1, aided by captured parts and intact missiles that failed to self-destruct.

Within weeks, teams at Wright Field in Ohio had unraveled the secrets of the V-1’s simple but effective pulsejet—a tube with a flapper valve, fuel injectors, and a spark plug, producing a deafening 900 pounds of thrust.

Whereas the Germans used steam catapults to launch their V-1s, the Americans opted for solid-fuel JATO rockets for their copy, dubbed the JB-2 by the Army Air Forces and the Loon by the Navy. The JB-2 went from drawing board to prototype with remarkable speed.

Ford Motor Company supplied the engines, Republic Aviation was tasked with the airframe, but the workload overflowed to Willys-Overland, the maker of the legendary Jeep. The differences from the V-1 were subtle—slightly larger wings, a different engine pylon, and a longer range-counting propeller. Inside, a simple autopilot, magnetic compass, and barometer guided the missile, while the propeller measured the distance traveled.

The first JB-2 launched from Eglin Field in Florida on October 12, 1944. Throughout the autumn and winter, more tests followed, including air-launched versions echoing German tactics.

The Navy, for its part, envisioned launching these missiles—now called the KGW-1 and later the LTV-N-2 Loon—from ships, submarines, and landing craft. By June 1945, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, head of the USAAF, listed the JB-2 as his third strategic priority after the B-29 and P-80, planning to unleash them against Japan before an invasion.

Even as the atomic bomb loomed in secrecy, Arnold saw psychological value in a missile barrage; despite evidence that such attacks hadn’t broken British or Belgian morale.

The war ended before the JB-2 could be used in combat, but its legacy was just beginning. The American V-1 became a vital training tool, teaching the Navy and the newly independent Air Force the ins and outs of missile technology.

Experimental launches continued in Florida, New Mexico, and at sea, culminating in the historic 1947 launch from the USS Cusk. The Loon’s moment on the deck of a submarine was a turning point—the dawn of a new era for undersea warfare.

The Loon and the Cusk: What Are They?

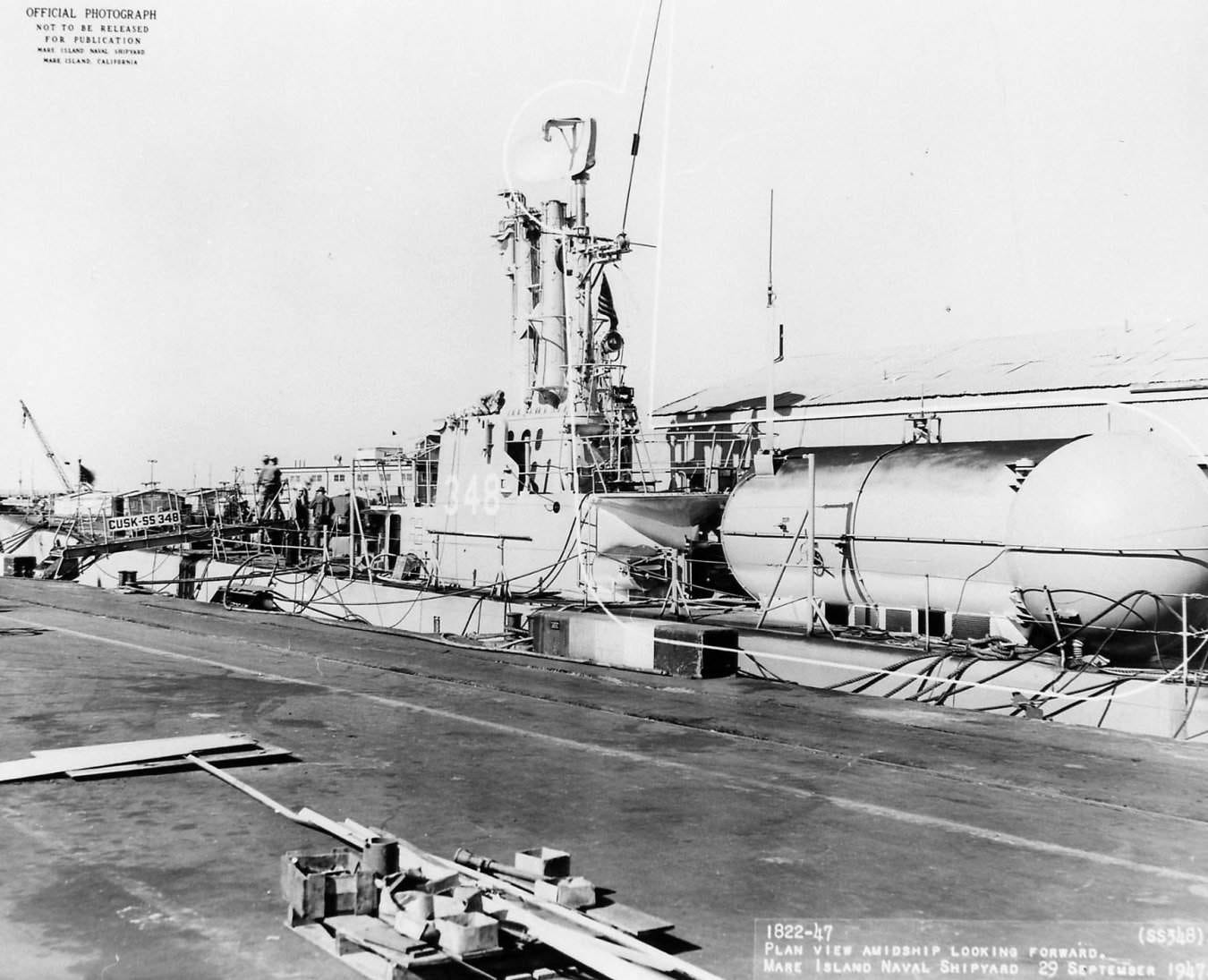

Cusk (SS-348) first touched water on July 28, 1945, launched by Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, and officially joined the fleet on February 5, 1946, under Commander P.E. Summers.

After leaving New London that April, Cusk ventured through the Caribbean before arriving in San Diego in June. That summer, she sailed north to Alaska, then settled into operations out of San Diego.

Cusk would soon make history: on January 20, 1948, she was redesignated SSG-348 and became the first submarine to launch a guided missile from her own deck—a bold step that paved the way for future ballistic missile subs.

Even after a major modernization at Mare Island in 1954, Cusk retained her role in missile development thanks to her specialized guidance systems. By May 1957, Pearl Harbor became her new home port.

Cusk continued to break ground in missile experimentation in Hawaiian waters, with notable cruises back to San Diego in 1957 and deployments to the Far East in 1958 and 1960, sealing her reputation as a pioneer in the evolution of undersea warfare.

Meanwhile, the Loon—also known as the JB-2 or KUW-1—was America’s answer to the infamous German V-1 “Buzz Bomb” of World War II.

Equipped with a pulsejet engine and able to deliver a 2,200-pound warhead over 150 miles, the Loon could be launched from the ground, ships, or even aircraft, its signature long tube pulsejet trailing behind.

The Loon and the Cusk’s Enduring Legacy

The V-1 and its American descendants also inspired a flurry of postwar experimentation. The U.S. Navy’s “Gorgons” were direct heirs to the buzz bomb legacy.

Though the Loon arrived too late to see combat in the war, it became a vital training tool, giving Navy and Air Force crews their first real experience with missile operations. Ultimately, the program was cancelled in 1950, but its legacy shaped early American missile development.

In fact, the late 1940s and early 1950s became a golden age for cruise missile development, as the U.S. military bet heavily on these technologies at a time when accurate guidance for ICBMs seemed a distant dream.

In these years, the focus shifted from the brute force of high-explosive bombs to the precision and reach of guided missiles. The promise of submarine-launched cruise missiles was clear.

They could lurk undetected beneath the waves and strike at a moment’s notice, fundamentally changing the calculus of deterrence. The lessons learned from the V-1 and its American cousins paved the way for the sophisticated missile submarines that now patrol the world’s oceans, silent sentinels of strategic balance.

The Loon and the USS Cusk may seem like footnotes in the vast history of American military innovation. But their story is one of daring improvisation, rapid adaptation, and the relentless pursuit of a technological edge. In the crucible of the early Cold War, these pioneering weapons helped define the future of naval warfare, setting the stage for the formidable undersea deterrents that would follow.

In the end, it was not just the missiles themselves, but the willingness to experiment, learn, and adapt that ensured America’s place at the forefront of military innovation—a legacy that continues to shape the world’s strategic landscape to this day.

In Case You Missed It

Photo Outlet

Every issue of Hangar Flying with Tog gets you a free image that I’ve taken at airshows:

Feel free to use these photos however you like, if you choose to tag me, I am @pilotphotog on all social platforms. Thanks!

Post Flight Debrief

Like what you’re reading? Stay in the loop by signing up below—it’s quick, easy, and always free.

This newsletter will always be free for everyone, but if you want to go further, support the mission, and unlock bonus content like the Midweek Sortie, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this flight crew flying—and I couldn’t do it without you.

– Tog